The role of antibiotics in treating bacterial infections.

The Importance of Antibiotics

Antibiotics are a cornerstone of modern medicine, essential in treating bacterial infections and transforming healthcare capabilities globally. Since the momentous discovery of penicillin in the 1920s by Alexander Fleming, antibiotics have become indispensable in reducing morbidity and mortality worldwide. These potent drugs are specifically designed to target bacteria, effectively eradicating them or inhibiting their growth and reproduction. Their judicious use has drastically changed the landscape of disease treatment, enabling what was once considered incurable to be addressed with a fair degree of certainty and efficiency.

How Antibiotics Work

Antibiotics function through various meticulously designed mechanisms to combat bacterial infections effectively. Among the different classes, some antibiotics, such as penicillin, focus on compromising the integrity of the bacterial cell wall. This disruption ultimately leads to the destruction of the bacteria, as it becomes unable to maintain its structural integrity. Meanwhile, other antibiotics exert their effects by inhibiting critical bacterial processes such as protein synthesis or DNA replication. By targeting specific bacterial functions, antibiotics ensure that they are ineffective against viral infections, which require entirely different treatment modalities. As a result, understanding the nuanced mechanisms of antibiotic action is fundamental in ensuring their proper use and effectiveness in treating bacterial infections.

Prescription and Usage

Antibiotics are typically available only through prescription to guarantee their appropriate and safe usage. This regulation is critical in preventing misuse and ensuring that the most effective treatment protocols are followed. Physicians carefully prescribe antibiotics based on the type of infection presented and the specific bacterial strain involved. Deciphering the exact cause and nature of the infection permits healthcare providers to select the antibiotic that the causative bacteria are most susceptible to.

For patients, adherence to the prescribed dosage and duration is paramount. Even if symptoms improve or resolve, completing the entire antibiotic course as directed helps prevent the emergence of antibiotic resistance, a significant and growing public health concern. Discontinuing treatment prematurely can allow surviving bacteria to adapt and become resistant to the previously effective medication.

Antibiotic Resistance

Antibiotic resistance stands as one of the most significant threats to the long-standing efficacy of antibiotics. It occurs when bacteria evolve mechanisms to withstand the effects of antibiotics, rendering some medications ineffective. The acceleration of resistance is primarily fueled by the misuse and overuse of antibiotics, not only in human medicine but also in agricultural practices where antibiotics are often used to promote growth and prevent disease in livestock.

The implications of antibiotic resistance are profound, resulting in prolonged illness, increased healthcare costs, and a higher risk of mortality from bacterial infections that were once easily treatable. This global challenge underscores the critical need for judicious antibiotic use and investment in new research to discover novel antibiotics or alternative treatments capable of outpacing bacterial evolution.

Preventive Measures and Alternatives

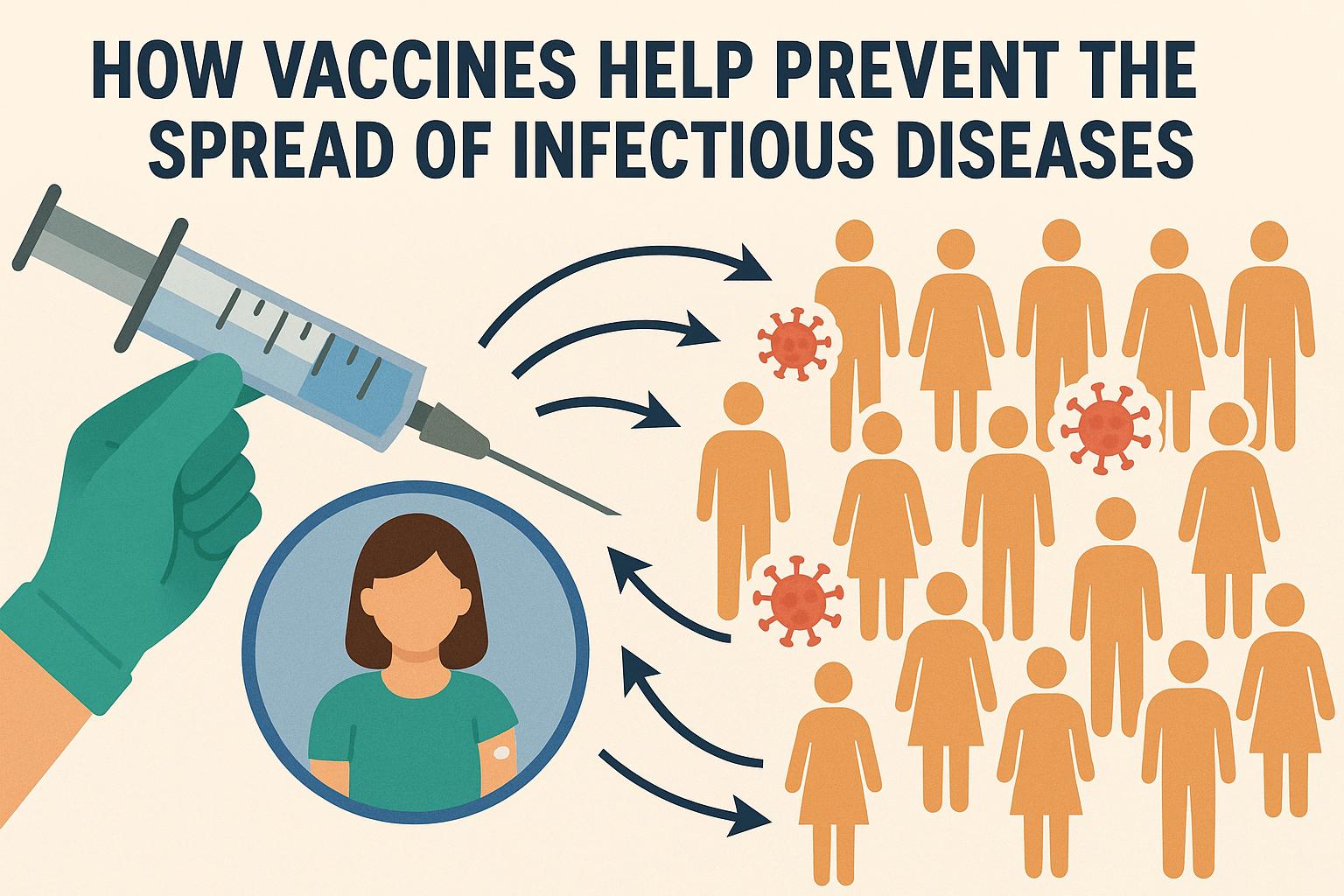

Emphasizing preventive measures and exploring alternatives is essential in combating bacterial infections and reducing reliance on traditional antibiotics. Vaccinations play a crucial role in preventing infections, thereby lowering the overall need for antibiotic treatment. Additionally, maintaining rigorous hygiene standards is fundamental in the prevention of infection transmission, thereby diminishing the incidence of bacterial illnesses.

Exploring alternatives is also important in reducing dependency on traditional antibiotics. Bacteriophage therapy, which uses viruses that infect and kill bacteria, offers potential as a targeted and precise method for treating bacterial infections. Similarly, natural antimicrobial agents are being researched to understand their efficacy in treating infections without contributing to antibiotic resistance.

Strategically integrating these preventive measures and exploring alternatives can significantly impact public health, helping to ensure that antibiotics remain an effective component of our medical toolbox for treating bacterial infections.

For those seeking more detailed information on antibiotics, their proper use, and ongoing initiatives to combat antibiotic resistance, reputable sources such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) provide invaluable resources. These organizations offer extensive guidance on antibiotic stewardship, educational materials, and updates on current research and strategies to mitigate the emergence of antibiotic resistance.

In understanding the significance of antibiotics, their mechanisms of action, the risks of resistance, and the importance of preventive measures, we forge a path towards preserving the future utility of these essential drugs. The coordinated effort of healthcare professionals, researchers, policymakers, and the public is crucial in combating bacterial infections and ensuring the continued efficacy of antibiotics for generations to come.